Sitting with my book manuscript, yes, no, maybe, a book of gentle editorial advice for poets, I am filled with a sense of rightness. I have pages and pages to complete, facts to check, and permissions to ask for; and yet, the feeling continues to be one of unadulterated joy. Until. What is it about human psychology, where alongside joy, we find doubt? The toothache is gone, but that hole in my mouth where my tongue gravitates, why is it so seductive? Usually I have enough natural rebellion in me to continue, to push through the doubt into the flow where negativity can’t breathe. Usually. Today I have allowed doubt her entrance. Not doubt about my intent. Or my ability. But about the current literary culture, and my place in that culture. I am what my high school psychology teacher called (as she looked directly at me), a late bloomer. I quit college to get married, and returned to school with a burning desire to learn. After years of attending part-time, I remember the exact moment while I was choosing items in the college bookstore, when I knew all I wanted to do was write. I’d had a modicum of success with words, and was bored with classes and the students who were already 15 years younger than me. I also had five kids of my own at home, all at various stages of growth and need. I put my over-priced bookstore items down and walked out. I didn't have a plan, I had a passion. My godmother knew my dilemma and asked the right questions: If you want to write, why are you majoring in something else? Why don’t you just write? You know that feeling where things click, where a person, or a mid-century modern, or a blueberry scone and cup of Sumatran coffee are meant just for you? That was my moment. I thanked the universe for the extreme good fortune of having this woman in my life, and for clarity. Bolstering my new image as an independent writer, I wrote two non-fiction books that were accepted and published with very little stress. The books were well-received; one is still being used at women’s retreats. I envisioned book after book written for the same publisher, easy success, even financial success. And then poetry found me. It changed everything. It changed me. Poetry filled the emptiness of leaving my beloved church, it filled the places I didn't even know needed filling. It became voice and it became prayer. There was no doubt, not one, that this was where I was supposed to be, tweaking lines, taking a word out and putting that same word back in twenty minutes later. This was where I was my best self. It has been that way ever since. Until now. Doubt. It assaults me with both hands around my throat. As I read through a copy of Poets & Writers or a best new poet’s volume edited by someone named Jazzy, I acknowledge that most of today’s published poets come with pedigrees, or rather, several degrees. I love education, what it opens in us, what it opens for us, but cannot add a degree to my own bio, and as co-editor of a small literary magazine, I feel rather naked admitting this. Recently, my husband and I, needing to investigate the Southwest beyond Denver, beyond driving due west into the Rockies, took off for Taos, New Mexico. The stunning views from the car and while hiking at 10,000 feet, the humility of the people, and the pull of open spaces, unearthed something in me. I brought that peace back with me to the city, let it slip down over my arms and hips and thighs. I let it hold me. Because I fell in love with the landscape, I researched a residency that would allow me uninterrupted weeks in that atmosphere, where I might complete my book. After downloading the residency application, the first question stopped me: Schools of Study (Do not list credits. List only time spent and degrees, if any.) I considered writing the inexplicable, not applicable, then thought better of it. The form languishes in a stack of papers. The doubts that assail most writers are massive; we are afraid we are not smart enough/ young enough/old enough/clever enough to find publication in an age of confusion, and specifically for writers, an age of extreme publishing confusion. We hope not having an MFA doesn't affect our chances for publication, unless we have an MFA, and then we hope our work is strong enough to honor that MFA. We are doubt-ridden beggars, waiting for some editor or publisher to grant us entry. And once we’re through their door, there is no guarantee, no assurance that our next poem or short story or book will get us through that very same door a second time. It is a maddening vocation. While talking with a good friend the other night, I found myself using that word several times. Because ours is not a hobby or a temporary distraction, not even what we do for praise and attention. It is our vocation. And my current fear that my lack of a degree is holding me back, is the reality I must live with and work through, because I won’t stop writing and I won’t stop submitting. It’s like parenting; you don’t get to stop in the middle of the job because it gets harder. And like parenting, there are several possible outcomes. As I fondle these slick pages of copy paper from Sam’s Club, paper with simple black marks, my simple black marks, I choose not to bow down to the god of doubt. I have no time for this. Even if my book isn't written 300 miles from home in an orange adobe casita, it will be completed. I will then pray some editor will understand what I’m attempting to convey with my words, and that she will bless me, in spite of no stamp of approval from an educational system, with her editorial pen, saying yes, yes, yes to my yes, no, maybe. Postscript: I dug through my papers, pulled out the residency application, and wrote not applicable in the blank. Yes, no, maybe is one third yes and one third maybe. Those are pretty good odds.

1 Comment

Listen to the moan of a dog for its master . . . Rumi continues, along with Rilke, to bring the infinite into my life, to help me see the world with more than cynical eyes. When his voice booms from the body of Coleman Barks, I recognize magic. It is the same awe I once felt in church, the same letting go of outcome, the same living fully in the moment.

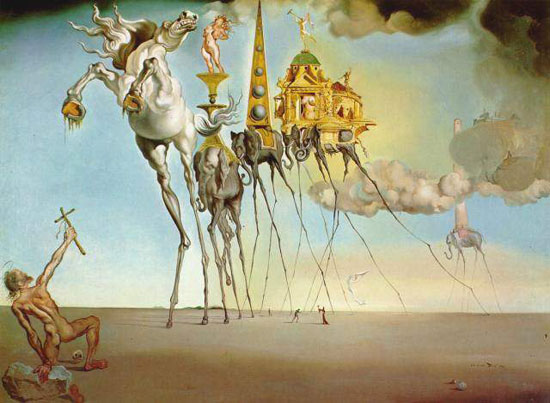

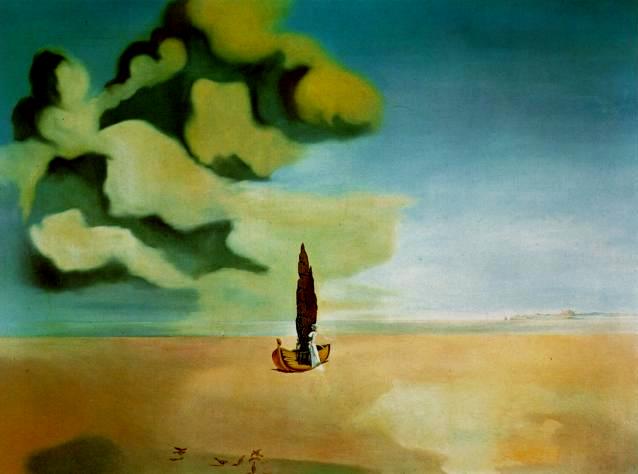

How infrequently we allow ourselves these moments. We choose to stay busy, our televisions spitting out programs, our iPhones feeding music into our heads, and when we sense the quiet coming for us, we open the door and invite chaos in for a long visit. I can’t write because . . . I can’t create because . . . As writers, as poets, our need for the quiet of emptiness is tenfold. To create there must be space around us, not just physical space but internal. In order to be a conduit of anything, we must learn to live in this silence, this opening into the unknown. We must become comfortable with ambiguity, unfinished sentences, projects that make sense only to us, and fresh ideas that take us far from home . . . What Rumi says about love dogs . . . Love Dogs by Rumi One night a man was crying Allah! Allah! His lips grew sweet with praising, until a cynic said, “So! I’ve heard you calling out, but have you ever gotten any response?” The man had no answer to that. He quit praying and fell into a confused sleep. He dreamed he saw Khidr, the guide of souls, in a thick, green foliage. “Why did you stop praising?” “Because I’ve never heard anything back.” “This longing you express is the return message.” The grief you cry out from draws you toward union. Your pure sadness that wants help is the secret cup. Listen to the moan of a dog for its master. That whining is the connection. There are love dogs no one knows the names of. Give your life to be one of them. It is this connection that I long for, the connection to Other and to other, and to the dog who sleeps at my feet, stretching the width of the bed, shedding her black hair on newly-washed flannel sheets. Coleman Barks reciting Love Dogs: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UF4_KZfIfVI  Have no fear of perfection - you'll never reach it. Salvador Dali This week we drove with our two oldest grandsons and another much younger grandson from Eugene, Oregon to Denver, Colorado. The older boys have three young sisters, so they know how to entertain a toddler. Still, as we left the hotel early on the morning of the second day of the road trip, even with prompting, the toddler sat down on the sidewalk and refused to budge. I have felt like that often in my own life, when fear trumped trust. Like really, you expect me to keep going, to get back in the car, back to work, to get back on the proverbial horse? I'd rather just sit this one out. But that is not the way it works. No matter our desire to skip participation in life, the horse is still waiting for us to climb onto its back. And it won't budge or get out of our way until we do. The past several months, whatever muses I usually summon to write poetry took a vacation of their own. I envisioned them swimming naked in the ocean, in sailboats waving lazily back to shore, mountain climbing, and riding bikes along the Pacific Coast Highway. One was on horseback, the animal wildly kicking up sand on the beach. And I was stranded on the side of the road, an observer. And then in the middle of our harried road trip a name jumped off a road sign and into my imagination. Burnt River. I jotted two stanzas and just came back to them this morning. And then I wrote a second poem not about rivers or fire, but about my parents letters to each other. Or rather my fathers letters to my mother, and the missing ones from her. The muse named "parents" had found me. My grandson had no choice, we strapped him back into his car seat for the long drive from Jerome, Idaho to Denver. I do have a choice, to continue with the work I have begun, or to sit by idly watching. The world continues to write, to create, to inexorably change no matter my choice, so it is far better to drag my little boat to the water's edge, jump in, and to sail into unknown waters. Not surprisingly, my poetry has always been found in those waters.  Poetry month, April in her infinite melancholy, has passed. I let her pass me by without attending one reading, without doing one collaboration, without buying one book of poetry. I did write one poem. And that poem was about not having words. I have gone to the birds for an explanation of the words becoming dross, flight not the only thing birds have to teach, their keen eyes watching over hot pavement, their intrepid waiting. I used to pray for more, writing "clarity" in my journal, beg for some trail of metaphorical bread crumbs. But May has shown me her mercy, giving me back, if not passion, a sure desire for words. Not only mine, but the poets we publish in Tiger's Eye. I think about them often, and often let them down. Someone is upset we held his work too long, another poet pulled her poem before we asked for it. A chapbook is published with errors, and we have to start over. These things are real and immediate, leaving me feeling that any job, paid or unpaid, literary or otherwise, is fraught with disappointment. Tenacity is needed. And vision. And plain old shoulder-to-the-wheel effort. And humility. Outside my window the wind is kicking up as the sun sets a little later tonight. Neighbors are coming home from work, a woman rides up with a Burly following behind. She unbuckles her small son and he climbs out, then she drags the bike and Burly upstairs. Someone speaks Spanish. Someone speaks English. A dog yips twice. And suddenly I'm grateful for the cool air, my husband chopping small red potatoes in the kitchen, the dog always constantly near. Such subtlety is where I choose to live, in the liminal places, the before and after that make us nervous. There are words here, there are worlds here, and possibly poems. Tonight, that poor damn dog the neighbors leave on their tiny back porch seems tragic and holy at the same time. I want to name him Lonesome, the name of my childhood German Shepherd. I want someone to let him indoors, to stroke his good strong head, to appreciate him. And that is it, appreciation. To be appreciated. To be seen. Heard. May is giving me ears to hear, and a voice to speak, and the sky is on fire with something I can't begin to name. It feels so much like autumn and yet I know the heat is coming, the stifling months of light and sweat and discomfort. But here in this moment, this unquenchable need to speak the unspoken, to speak of the unspeakable. Words. My words. Never give up. And most importantly, be true to yourself. Write from your heart, in your own voice,  A good friend, Laura LeHew, has a small poetry press, Uttered Chaos, based in Eugene, OR. She sent me her most recent publication, Turn, an anthology of poetry in which the months of the year are highlighted. I remember attending a critique group where we all admitted to having written "November poems." And these poems were moody, introspective. Were we reacting to the coming darkness, the anticipation of becoming more insular, more solitary? November's wistful poem is markedly different than May's exuberant one. Or the heat and humidity of an August poem, the weariness of continual sun and light. I am going to write a review of Turn, but here I am more interested in the larger story of how each voice in this book is (gratefully) unique. When we think we have to write like Billy Collins or Mary Oliver or Sylvia Plath, we've missed the point. We may be able to mimic style and voice to a degree, but we will never write their poems as well as they do. As I read Jane Hirshfield's poems the other day, I became envious; I wanted to write her poems. I wanted to capture what she'd captured in just the way she'd captured it. When I returned to the world of limitations and differences, I was grateful to this woman for giving so much of herself to poetry, for living such a particular life that whatever she writes is astoundingly unique. from "The Promise" by Jane Hirshfield Stay I said to my body. It sat as a dog does, obedient for a moment, soon starting to tremble. As writers, as poets, our need is to dig deeper into our November selves, to expose and turn over whatever we've buried, whatever asks for May's exposure. And when that material frightens us, and it will, we'll know it is the rich detritus of creation. This is what makes our poem our poem. No one else has this exact experience, the corresponding emotions, or the singular voice that only we possess. In reading through Turn, I could not choose one poem above another. But "November, Late" by Amy MacLennan, with its subtle grace, its forgetting of self, is my current favorite. The author is talking about losing someone, a final gift, but throughout the poem she works deftly with the image of leaves. from "Novemeber, Late," by Amy MacLennan Daylight will come back with new leaf folds on the tips of branches. I watch for them even now, even as the dying ones remain. Although I might have a similar experience, I could never have written this poem in this way, its inflections, its tone, belong solely to the poet. As I continue on through Turn, I am as excited to find differences, as well as similarities. Like the seasons, there is beauty in sparseness as well as in abundance, in the lyric as well as the narrative.  Social media is a giant distraction to the ultimate aim, which is honing your craft as a songwriter. There are people who are exceptional at it, however, and if you can do both things, then that's fantastic, but if you are a writer, the time is better spent on a clever lyric than a clever tweet. Bryan Adams In a world of instant gratification through social media, at what point does this major distraction distract from the quality of our writing? Do we twitter, pinterest, facebook and ning our way through the day, or do we use these communication tools to occasionally make contact with the people we care about? Should we, as writers and creatives, be even more concerned about the effect of constant and easy communication? And if we are adding to the overall online noise, what is the quality of that noise? A few years back, the word "platform" became the new obsession for writers. You didn't even need a completed manuscript, you were encouraged to build your platform, and then you could worry about what you were offering the world. Who you were, or made yourself appear to be, was the selling point, not what you wrote, or even how well you wrote it. It seemed absurd to me, a kind of backwards approach to creativity. Get an audience and then create something! The only way this approach is valid is if the end product of creativity is just that, a product. We can argue that of course a painting or a book, a Florence + the Machine CD or a well-crafted bentwood rocker is a product. Yet doesn't the quality of the commodity matter more than how much attention it receives? If 200 people "like" something on facebook, does that make it more viable? What frightens me is that we might lose the deep contemplative selves that need quiet rooms, disconnection from electronics, and large swaths of time in order to have thoughts worthwhile enough to share. If our communications become primarily superficial, where in this electronic rabbit's hole is there room for empathy, for compassion? Not only do these distractions detract from our ability to create freely and wildly, they ironically distance us from one another. Are we short-circuiting our adult brains, just like kids parked in front of Sesame Street? No one questions PBS-wisdom, when the early childhood experts explain that children have short attention spans, and shooting images and words and bright characters at them is the best way to program their malleable brains. We might ask those experts if learning how the adult world works in slow, boring time isn't a better preparation for living in the adult world. Sesame Street to twitter is not a big leap. We adults build our web sites, create blogs, such as this one, and maybe we even have followers on the quick and dirty sites. Our every thought broadcast for others to consider. But what of the content? Can we in 140 characters communicate any more than self-interest? Do we touch or help or change one another's lives by posting the meal we just ate or the hand bag we just bought? Do you really care if I did 50 reps per arm at the gym? Okay, 30. I recently opted out of facebook. I assumed my adult children would eventually call me, my friends too when they figured out I'd gone missing. As for the dozens of new "friends" I'd befriended, they would not truly miss someone they'd never met face to face. I'll maintain this site and my business site . . . and I'll communicate more intimately with people. I'll call them or email them or write them a letter. People still do that, right? As writers, we know what it takes to create our best work . . . each of us having a different set of quirky needs and habits. I found early on that I could not have music playing while I wrote, the lyrics kept me from deep concentration. Discovering that social media, as seductive as it is, has the same effect on me, it makes sense to walk away. I may not be following the populace, and the populace is definitely not following me, but if you and I pass on the street, recognize one another and embrace in friendship, that is enough of a platform for me.  One builds a house of what is there . . . Charles Tomlinson December marked one year of living in Denver . . . nothing has occurred as we’d expected, and nothing is going as planned. Oddly, I am getting used to being unmoored. The poems I wrote during that chaotic twelve-month period are stark, more narrative than my usual style. The only explanation I can come up with is that when you’re up against the wall, you don’t write lyric poetry. I quite literally felt I was nailing down each word, each line, so it wouldn't get away. The theme of my poems has been predictably, home, houses, moving, change . . . and it runs continuously through this what I'm calling, "a small chapbook." Only 26 pages, counting all of the front matter. What I’m feeling is relief, relief that in spite of a year of immense change, I produced a body of work. I've been telling people I'm not writing, and I'm not writing as I normally would, batches of poems created in periods of literary passion; but instead, a slow and steady stream of words turning to lines turning to poems. Where we live, how we live, the people we let in, the people we turn away, all of these things matter in life, and in our writing. The landscape matters. I used to question poetry of place, thinking it simple. I've come to see that all poetry is landscape poetry, all is impacted my our exterior climate, as well as our interior. Someone told me they couldn't wait to read my "dry" poems that would come from living in the mile high city. And possibly these narrative poems are my dry poems, they definitely lack the emotionalism of my Oregon poems. They also lack water, which mirrors this land of stark, dry beauty. I'm sending the manuscript out, I'm filled with expectation that someone will take it, print it, give it wings. And now I'm writing haiku, which is centering me, and a non-fiction book that is un-centering me. This is creative tension, which has always been my inner landscape, the struggle to understand, to nail down a feeling, an image. As I type, there is a squirrel out my window, his tail just gently moving, then he bites himself and hugs his tail . . . and I am transported somewhere else. And this, this moment, is its own landscape. squirrel in winter sprinting from branch to branch expecting spring  Back from OR and CA. The holidays stretched out to include two weeks of working with my friend and co-editor, JoAn, in CA. We accomplished a lot, published the latest issue of our journal, read submissions for the next one, contacted poets . . . and in the back of my mind was my own writing. I'd written one poem on the road trip from CO, and another my last full day in CA. In-flight, after reading a particularly negative article in Poets and Writers, I knew one reason I wasn't writing, why it seemed more a chore than a joy. I had fallen into the world of magical thinking. Someday I would be known, published in the bigger journals, and make money from writing poetry. I'm an editor of a small press poetry journal, I should know better. Instead of despair, this latent realization brought extreme relief. I've been stuck in someone else's model for success. I can now relax and return to my previous mind-set where writing is for the joy of it, not for the pay-off of publication or an occasional check in the mail. I can go back to daydreaming and observing and just being myself. And if something does open, some wider arena, I will enter it knowing I've earned it. Months ago I bought a used copy of the book, Flow, by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. This from chapter 6: A person who becomes familiar with the conventions of poetry, or the rules of calculus, can subsequently grow independent of external stimulation. Sometimes having control over such an internalized symbol system can save one's life. It has been claimed, for instance, that the reason there are more poets per capita in Iceland than in any other country of the world is that reciting the sagas became a way for the Icelanders to keep their consciousness ordered in an environment exceedingly hostile to human existence. Isolated in the freezing night, they used to chant their poems huddled around fires in precarious huts, while outside the winds of the interminable arctic winters howled. If the Icelanders hadn't spent all those nights in silence listening to the mocking wind, their minds would have filled with dread and despair. By mastering the orderly cadence of meter and rhyme, and encasing the events of their own lives in verbal images, they succeeded instead in taking control of their experiences. Taking control of our experiences. No wonder the proliferation of MFAs in America. We as a collective are living in a hostile environment, bombarded hourly by dire political and environmental predictions. We have recently exited an "end of the planet" mania because of an ancient calendar's ending. Now we are taking in the aggression of gun control arguments. Creating order with poetry, as well as any other symbolic system, makes sense when our outer world becomes threatening. I usually avoid new year's promises, but this year I have committed to re-connecting to my writing life. Not the magical one I found myself in, but the real one, where writing is a joy and a passion, where the work takes precedence, and all else is icing on the poetic cake. All compounded things are impermanent. --the Buddha Of all of the tragic images coming from NY and NJ, the one of a widow clutching a piece of china, all that was left of her material world, made me cry. Even the newscaster had tears in his eyes. She seemed so alone, she'd lost her husband, and now her house was gone, just gone. She said she wanted something to take with her. When she found the broken plate, she was satisfied; she could leave the wreckage that used to be her shelter. The parting shot was her walking slowly toward a relief group, the plate still held to her chest. I've thought of this woman, and more despondently of the woman whose two sons were swept from her arms, the father and daughter who stayed behind because during Irene their home had been vandalized, and now both are gone. I can't help but consider the thousands of people permanently affected or displaced by this massive storm. As co-editor of a small poetry journal, I expect poems to start coming in that contain weather, loss, broken things. But then most of our poems contain the broken elements of our lives. We write about love, knowing how fragile it is; we write of autumn's yellow leaves as they release themselves from the trees and fall to be swept away. Maybe we write to save that ideal moment, that shared whisper, that image of autumn becoming winter. Impermanence. We hate the word, we hate the idea of it, and we often spend our lives denying its existence. How ironic that turning and facing impermanence gives life an unexpected sweetness. Accepting that everything and everyone is made up of exhaustible materials, including ourselves, both terrifies and comforts us. As writers, we work with our word lists, we scribble our thoughts, choose line breaks and better words. We submit our work to be heard, but I suspect that seeing our thoughts in print is also concrete proof that we matter. It is our little stab at immortality. It is our broken plate, something to hold to our chest when the world has become utterly incomprehensible. No matter our losses, we'll keep writing, and we'll keep sending, and we'll keep pushing that submission manager button, the one that still seems ludicrous and unreal. Once in a while someone will tell us our work made them think or cry or reconsider. And in that moment we will be as permanent as we're ever going to be.  Like the priest who said, All of my sermons are about the things I need to work on, when I give writing advice, it's because I need to work on that same area. I'm asking you to consider the possibility that the reason you haven't completed your poem, collage, book, thesis, letter to the editor . . . is because it's the wrong project. It isn't that you can't complete what you've begun; it’s because you are no longer excited about it, and on a visceral level you already know this. You just haven’t given yourself permission to dump the project. I've had inspired projects where the muse skittered across the page so quickly I couldn't keep up with her. But once I became immersed in the project, I knew it wasn't going to be fleshed-out. I either didn't have the necessary stick-to-itiveness, the skill, or my desire waned to the point that facing the project was like looking into a pit of hissing snakes. This past year, my desire to write poetry lessened considerably. I wasn't blocked. It was worse than that: I was disinterested. So I began writing a novel, and when that project started hissing at me, I quit. I loved my characters, I loved their long, clever conversations; but I didn't care enough to follow them to the ends of the earth, let alone the end of the book. So I abandoned them. Out of nowhere (in other words, the thought was slithering around in my head all along and I'd ignored it) an idea came to me for a non-fiction book about writing and submitting poetry. The idea thrilled me. It incorporated everything I'd learned over the past ten years, while co-editing a small press poetry journal, as well as my own conflicted experiences in the uncertain world of publication. The snake-hissing lessened considerably as I thought about the book's possible content, and stopped entirely when I began the writing, the editing, and the all-out believing that my fledgling project deserved. Instead of fearing the pit of snakes, I began playing my pungi until the snakes danced for me. Ideas are exciting, like new love, all titillation and flirtation. Often these flirtations turn into concrete published poems and books. But sometimes we need to let go of the very thing we thought we loved, just stop in the middle of the endeavor and give it a big heave-ho into the abyss. It challenges what we've been instructed to do since preschool. It goes against our finish-everything-you-start mentality. And it feels wonderful. If what you're working on doesn't thrill you, if the work seems too much like work, stop chastising yourself. Set it aside and consider something outside your normal venue. If you write poetry, try essays, if you write essays, try short stories. If you’re tired of writing, pick up a paint brush. Don't allow frustration or ennui to stop you from expressing yourself. Bust out your pungi and start playing. |

Archives

October 2022

AuthorMy writing often deals with the environment, my poetry filled with allusions to natural and man-made disasters. I have unlimited hope though; there is just too much wonder in this world to become a defeatist. To quote Margaret J. Wheatley, '"Hopelessness has surprised me with patience." Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed